The Future Lab

What a global survey of scientists says about developing tomorrow’s research buildings.

The commercial life science markets are currently facing challenges, with availability rates reaching 30%. However, the long-term outlook for this sector remains strong. In this evolving landscape — where technological advancements are transforming research methodologies — it is crucial to understand the needs and preferences of scientists. And yet, few surveys have taken a holistic look at what researchers require in the workplace.

To address this knowledge gap and further explore ways to improve research facility design, the architecture firm NBBJ and the New York Academy of Sciences — one of the country’s oldest and largest scientific societies — conducted a global survey of scientists throughout the summer of 2024. The Future Lab survey examines the work habits and built environment needs of 1,059 scientists representing a diverse cross-section of disciplines, career stages and geographies.

Survey graphic courtesy of NBBJ

The Future Lab survey’s key findings can help drive the design of next-generation research spaces that are flexible, improve well-being and perform more sustainably. Given that the survey found 65% of scientists consider workplace design to be a central factor in choosing an employer, the following insights offer a guide for creating life science developments that attract and retain top talent.

What Do Scientists Want in a Lab? Start With Collaboration

The survey started by asking scientists which elements are most important to them in their primary research building. This is perhaps the most important design consideration when weighing where to make investments and how to attract and retain tenants.

Not surprisingly, scientists prioritized spaces designed for collaboration more than their physical comfort. Across various regions, disciplines and career stages, the availability of collaborative spaces ranked as the top priority. Areas for focused individual work and adaptable, flexible spaces were also frequently identified as critical needs (respondents could pick three options):

- Space to collaborate with others: 49.7%

- Adequate space for individual work: 47.3%

- Flexibility and customizability to meet your needs: 43.4%

- Space to socialize and build connections: 41.5%

- Physical comfort (including elements like seating, temperature and air quality): 41.3%

- Views of nature or outdoors: 40.7%

- Convenient amenities: 33.4%

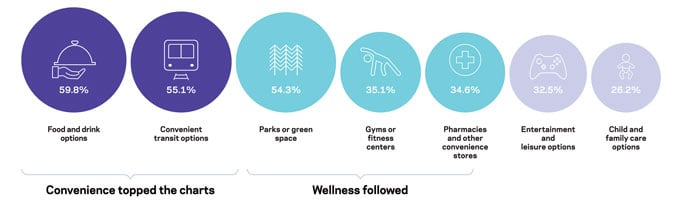

The survey asked scientists to prioritize a list of common amenities. Those focused on convenience, such as food options and accessible transit, were rated as the most important, followed by amenities that promote wellness (see graphic above).

Proximity to Researchers — Even at Other Institutions — Is Paramount

The survey asked scientists to evaluate the importance of being within walking distance of other scientists inside and outside their organization.

A strong consensus emerged (82% of respondents) that being physically near colleagues is critical for most scientists. Additionally, a clear majority (66%) value proximity to scientists in outside organizations, with this priority being even more pronounced in highly interdisciplinary fields such as engineering.

Given the importance scientists place on proximity to one another, clustered research buildings designed to foster interaction and relationship-building are particularly attractive to tenants. While social areas and amenities are commonplace, one often underutilized asset is the surrounding landscape. Features such as outdoor walking paths, rooftop gardens and indoor-outdoor spaces can provide informal opportunities for connection and socialization beyond the lab.

Scientists Report Their Buildings Can Do More to Support Well-being

Research has shown that office buildings impact the mental and physical health of their occupants. To investigate this connection, the survey asked scientists to assess how their current research building affects their well-being.

Only one-third of respondents believed that their current building adequately supports their physical and mental health. Considering the substantial effect that physical and mental well-being has on both individual performance and organizational success, this percentage should be significantly higher.

The survey suggests life science developers could differentiate properties by doing more to support the well-being of scientists. How can this be achieved? Part of the answer lies in neuroscience. Through initiatives like NBBJ’s partnership with developmental molecular biologist Dr. John Medina, research building design can target elements that directly enhance well-being — such as fostering personal agency, encouraging movement and connecting people with nature.

Technological Change Requires Rethinking the Cluster

Technologies like AI and automation are transforming science, but to what extent? And what implications does this have for life science clusters? To explore these questions, the survey asked scientists to what extent technology is disrupting how they work.

Scientists across the board recognized that technology is changing how they work, even if only slightly. Interestingly, 22% reported that AI, automation and other technologies were having no impact, with life scientists representing the largest percentage of this group. When asked to predict the impact over the next five years, 87% anticipated a shift toward “slightly” to “very disruptive,” reflecting a dramatic increase in expected change.

Remote work technologies are also enabling new modes of collaboration and research. Scientists reported that a significant portion of their work — 59% — could be done effectively from a remote setting.

With the rise of technologies like cloud labs, there is a clear opportunity to reorganize life science developments around the collaborative spaces scientists prioritize. As technology continues to decentralize research, this may also require rethinking life science clusters less as centralized hubs of scientists, labs and technology, and more as networks of locations, featuring collaborative hubs, retreat centers or other locations driven by lifestyle amenities, all supported by cloud labs and other technologies.

Lab Facilities Are Flexible Enough for Today, But Not for Tomorrow

Science is constantly evolving, which means that laboratories need to be more flexible — not only in the short term but also to adapt to changing market demands over the long term. With this in mind, the survey asked scientists if their primary science building is adaptable enough to meet their changing research needs.

Flexibility ranked as the most important building feature for specific demographic groups — scientists in North America, engineers, and those in advanced stages of their careers. Despite this, the survey revealed that over 40% of scientists think their current building lacks sufficient flexibility. When lab spaces can be rearranged on demand, scientists can maintain the pace they need to make critical breakthroughs without pausing for renovations.

The Regenerative Lab, developed by NBBJ, can be disassembled and reconfigured to adapt to shifting market needs. Image courtesy of NBBJ

Even if most scientists feel their current building is flexible enough, developers and owners must consider whether that flexibility will remain true in five or 10 years. To explore how labs can adapt over time, NBBJ developed the Regenerative Lab, an evolutionary concept for a people-focused, sustainable lab. Built using a hybrid steel and cross-laminated timber structure, the Regenerative Lab can be disassembled and reconfigured to adapt to shifting market needs, evolving from a lab to office space or even residential use as demands change.

Researchers Want More Sustainable Buildings

Labs are some of the most energy-intensive buildings, making sustainability a pivotal design consideration. The survey asked scientists how important it is that their primary science building is sustainable.

Eighty-three percent of scientists expressed a strong preference for sustainability, reflecting one of the highest levels of consensus in the survey.

With an estimated 60% of labs needing energy-efficient upgrades, this gap between scientists’ interest in sustainability and the actual performance of their labs represents a key market opportunity. According to an article from AIA California, reuse and renovation with system upgrades can reduce a building’s embodied carbon 50-75%, but this approach is sometimes overlooked as a strategy for achieving more sustainable buildings. Tools like NBBJ’s open-source ZeroGuide can help developers and owners calculate the potential carbon benefits of renovation, along with the carbon equivalent of all project-related emissions.

The Future Lab survey reveals many insights while raising new questions — such as how neurodiversity and generational differences influence scientists’ needs in the built environment. The hope is that this research will contribute to the creation of market-leading life science developments that are healthier, more sustainable and more adaptable than ever before.

The full survey, including all questions, responses and additional demographic breakdowns, can be downloaded at nbbj.com.

Cathy Bell is the firmwide education and science practice leader at NBBJ. Brooke Grindlinger is the chief scientific officer at the New York Academy of Sciences. Ryan Mullenix is the firmwide corporate practice leader at NBBJ.