Parking and the Return to Office

The demand for parking in downtowns remains hard to predict.

The growth of working from home during the COVID pandemic era has transformed American work on a scale similar to the shift from a six-day to a five-day workweek in the first half of the 20th century. The downside is that offices have been left empty and nearby businesses that depended on the daily influx of office workers have struggled to survive. This shift has dramatically impacted every aspect of commuting and therefore made it more difficult to gauge how much parking is sufficient, especially in downtowns.

Many in the office sector hoped that once it became safe for workers to return, a recovery to normal would soon follow. That has proved to be optimistic.

Kastle Systems, which tracks access activity data in 2,600 buildings and 41,000 businesses across 47 states, has been analyzing the data to identify trends in how workers are returning to the office. In its workplace occupancy barometer for April 22, Kastle reported a 51.9% occupancy average across 10 major metro markets, with a high of 67.4% in Austin and a low of 42% in San Jose (the Philadelphia, San Francisco, Los Angeles and Washington, D.C., metro areas also logged occupancy averages of less than 50%). There were wide swings in occupancy depending on the day; for the week of April 11-17, Tuesday showed the highest average occupancy (60.9%) and Friday the lowest (34.1%).

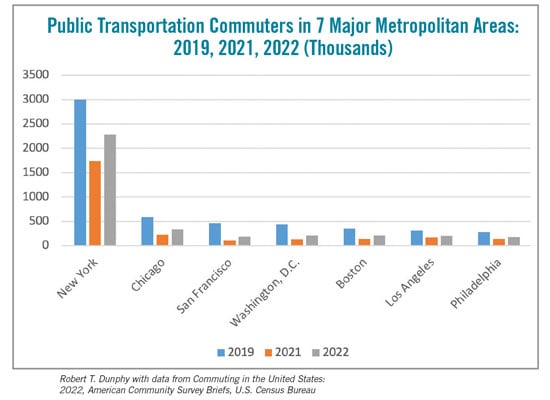

Transit Takes a Hit

With the decline in office workers, there are fewer commuters using transit. From 2019 to 2021, the share of workers dropped in half, fueling a catastrophic decline in transit ridership nationally. A U.S. Census Bureau survey found that about 70% of transit commuters living in metro areas lived in one of the seven “transit heavy” metros: New York, Chicago, San Francisco, Washington, Boston, Los Angeles and Philadelphia. These markets lost 3 million daily commuters between 2019 and 2021 and had regained only 1 million by 2022.

Slow Return to Work and the Toll on Downtown

Slow return to work can create excess office space and in turn, lead to declining real estate values and lower tax assessments. This is a special predicament for downtowns, whose office workers have been reluctant to return. According to an October 2023 report on downtowns published by Center City District (Philadelphia) and based on data from Placer.ai, which generates estimates from mobile phone data, San Antonio, Nashville, Midtown Manhattan and San Diego had recovered more than three-quarters of their nonresident workers in the second quarter of 2023 compared to the same quarter in 2019. The lowest worker recovery rates for the same period were in the Western cities of San Francisco, Portland and Denver, all hovering a little above 50%.

Before the pandemic, most downtown office markets were outperforming their suburban counterparts. This long-term trend changed dramatically between 2019 and 2022, as the average downtown office vacancy rate climbed from 10% to 16.2%. Over the same period, the average suburban office vacancy rate also increased, but from 12.1% to 15.4%.

A University of Toronto study of 67 cities across North America, also using cell phone data, found that cities with lower commute times and a lower share of jobs that could be performed remotely generally did better with worker recovery.

Impacts on Commuting and Parking

While real estate values affected by the slow return to office are a concern for owners and local governments, the associated decline in parking is a concern for office owners and parking operators alike.

The NAIOP Research Foundation report “Hybrid Work and the Future of Office” cited a 2022 CBRE survey noting that shorter commute times and the availability of parking were the two top factors that would make frequent office visits more desirable. Changes in commuting patterns helped to reduce travel times by 8% to 9% in Washington, San Francisco and Boston, according to a 2023 U.S. Census Bureau report. In addition, more commutes are now completed outside of traditional rush hours, making unexpected delays less likely.

Stacey H. Mosley, director of research for Brandywine Realty Trust, observed that parking utilization in downtown Philadelphia is quite high, as people who previously commuted via regional rail/mass transit have leaned into driving. “Brandywine’s parking division, BexPark, is doing quite well amidst the steady acceleration of return to the office,” Mosley said. “BexPark is a complement to our transit-oriented developments, providing optionality for those visiting our properties.”

John Dorsett, senior vice president for Walker Consultants, a nationwide practice with substantial experience in parking, said, “It will take time for things to sort out, if they ever do. Even though parking volumes are still down, parking revenues have recovered in some places because of rate increases. We have clients converting office to retail or housing, which supports a trend advocated by cities.”

“How much parking is needed is a moving target,” said Brett Wood, a consultant from St. Petersburg, Florida, who served as interim director of the Birmingham Parking Authority in Alabama. “In the past, a fully occupied building with maybe 15% absent could anticipate 75% to 80% parking pre-COVID versus perhaps 50% now. Mixed-use districts have better appeal to users and are suitable for shared parking, which reduces space needs.”

Wood believes that excess parking in downtowns is an opportunity for adding housing and that the kind of shared parking common in mixed-use districts is better adapted to the new markets, where the different uses have different peaks, allowing the same space to serve different users.

The Future of Parking

The recovery of parking, especially in downtown districts, is linked to the office recovery, but dramatic changes offer opportunities to rethink outdated parking policies. There are several possibilities worth consideration.

Explore shared parking. Most parking in the United States is provided exclusively for single uses and is typically free. Shared parking makes it possible to take advantage of the different peaks for office, retail and restaurants so that combined facilities can serve more users with fewer spaces. It may be possible, for example, to reconfigure some office parking to serve downtowns where visitors have returned while workers largely have not.

Investigate differential pricing. Differential pricing can help meet the changing office market, which has tended to be locked into monthly parking permits. Workers who are in the office only two or three days per week need a different price that makes sense — perhaps daily or maybe for multiple days each month.

Capitalize on existing parking to serve new housing. There is significant interest in building new housing in downtowns to meet demand. At the same time, building new parking is often cost-prohibitive. Because many workers have not returned to downtown offices, there is existing parking available that would cost $20,000-$40,000 per space to build new. These spaces are precious resources that could serve new uses.

There is a growing understanding in the transportation profession that too much parking is required in new developments. Reused and shared parking help to decrease the cost of development and create opportunities for new infill developments that can be financially successful.

Robert T. Dunphy is a transportation consultant and an Emeritus Fellow of the Transportation Research Board.