Transforming a Textile Mill Into a Vibrant Mixed-use Community

The Judson Mill District honors Greenville, South Carolina’s rich textile manufacturing history as it weaves a new plan for the future.

Greenville, South Carolina, once styled itself the “Textile Capital of the World.” While it might be difficult to quantify that superlative, there’s no question this small city along the Reedy River in the foothills of the Blue Ridge Mountains had ample claim to being one of them.

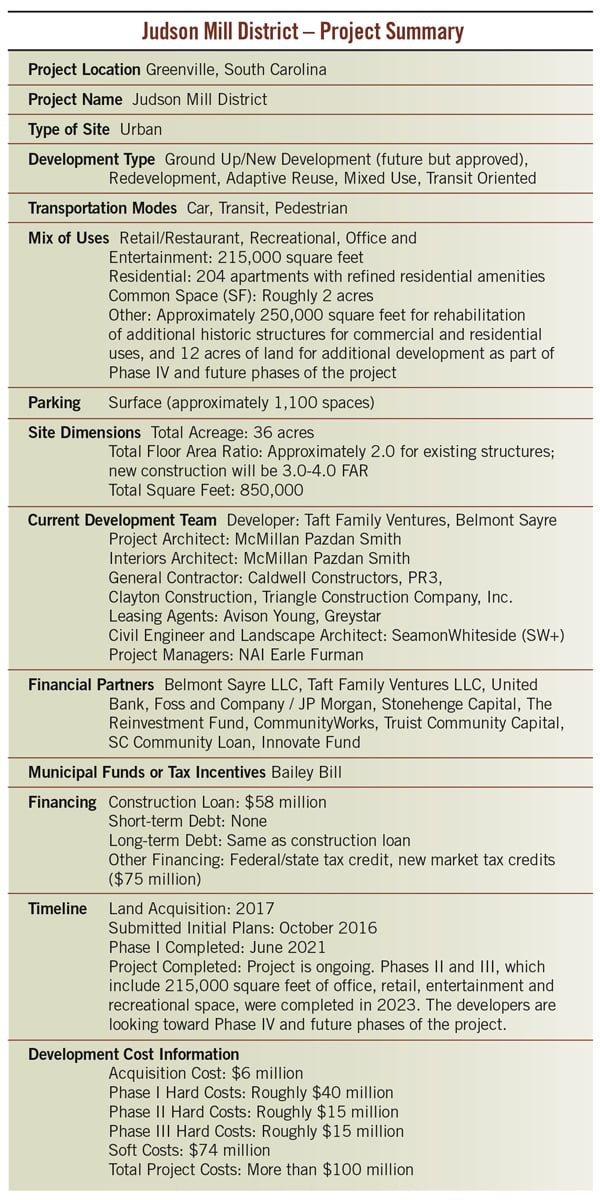

The city and its surrounding landscape once contained 18 textile mills, only two of which remain operational today. Four of the mills burned down or were demolished, but the rest remain standing, and they have proved to be excellent fabric for reuse. At least nine have been converted to new functions, including residential, office and mixed use. The most recent conversion is Judson Mill, an 800,000-square-foot complex that has returned to life as a mixed-use project containing apartments, retail, offices and more.

A Century of Industrial History

Adaptive reuse is often an undertaking for buildings that have long sat dusty, but this wasn’t the case at Judson Mill, which produced textiles from 1912 until 2015. Renovation of the mill began in 2019 as a project of Belmont Sayre Holdings of Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and Taft Family Ventures of Greenville, North Carolina. The project was designed by the Greenville, South Carolina, studio of McMillan Pazdan Smith Architecture.

A variety of exterior spaces have been constructed, including private patios, courtyards and new circulation paths that connect the buildings. Christopher Decker, courtesy of Triangle Construction Company, Inc.

The mill was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2018. Three original 1912 structures remain — the main mill, the picker room and the weave room — with a number of additions from subsequent decades, some built as late as the 1990s. The original facilities were designed by Lockwood, Greene and Associates, a firm that built eight of Greenville’s mills. The designs were highly functional, focused on supporting the fabrication process. They are defined by thick masonry, load-bearing walls, large windows, and timber and steel framing to support the considerable loads of machinery and textiles. Architectural details were simple and sparse, but the ensemble retains considerable historic distinction.

Whereas prior mills had been built as tall structures — inefficient in that they required moving materials up or down multiple stories — Judson Mill’s design was “modern.” At only two stories high, it was designed to facilitate the easy transfer of fabrics and other products. There were other practical reasons for limiting the height to two floors: Picker rooms, where fabrics were stretched, generated tremendous static electricity and easily caught fire.

The mill’s layout reflects a century-plus of industrial history. Separate buildings were gradually linked and expanded to ease integrated manufacturing processes and the rise of centralized air conditioning and heating. The complex gradually developed into one immense amalgam that over its life span produced everything from blankets to sheeting to slips to camouflage fabric for the U.S. military.

Historic Reuse

Belmont Sayre, a real estate investment and development company that specializes in the adaptive reuse of historic buildings, knows a thing or two about mill conversions. The company has worked on similar warehouse projects in recent years in the neighboring state of North Carolina, ranging from the American Tobacco live-work-play complex in Durham to CAM Raleigh, a contemporary art museum whose home is a converted forge and welding company warehouse dating to 1910. Taft Family Ventures has also worked with similar structures, notably the Clayton Spinning Mill in Clayton, North Carolina.

The Lofts at Judson Mill opened in summer 2021 and were nearly 100 percent leased within 10 months. Kevin Ruck Photography, courtesy of Judson Mill District

Belmont Sayre acquired the Judson Mill project in 2017 alongside financial partner Matt Springer, principal at Madrock Advisors. In 2019, Taft Family Ventures, a real estate investment and development firm, joined with Belmont Sayre to transform the historic textile mill. They purchased the site directly from industrial manufacturer Milliken for $6 million.

As Belmont Sayre President Ken Reiter observed, mill renovations in the South have taken on steam in the past few decades. “It’s been a relatively recent phenomenon in places like Charlotte, Richmond, Durham, even Atlanta. What was happening in the Northeast and the Midwest is making its way to the South. Previously, there wasn’t the kind of density to support this redevelopment. A lot of those people now want to live in a more urban setting.”

Belmont Sayre’s calculus for approaching these projects begins by evaluating the state of the buildings, which in the case of Judson Mill, was good. The company then considers if a local market will support a range of tenants (different in each case), whether neighborhood and community support is present and, finally, if tax credits are available.

Historic reuse makes eminent financial sense, with federal, state and local incentives (in this case, a specific Greenville County measure to incentivize mill conversions) invaluable in undergirding these projects. These are vital from a financial standpoint, Reiter said: “You need all of that to offset the extraordinary cost and complexity of doing these types of projects.”

The Innovate Fund, a community development entity in Greenville, South Carolina, allocated $16.5 million in New Markets Tax Credits, making the Judson Mill redevelopment its largest investment. Source loans came from Reinvestment Fund and Community Works. The project also utilized federal and state historic tax credits and additional credits from the South Carolina Textile Communities Revitalization Act.

An overview of the layout of the Judson Mill District. Judson Mill District

The Judson Mill District was a substantial undertaking. “It rivals anything … most people have done,” Reiter said. “It’s almost a million square feet. That’s a big project no matter where you are, [but] especially for Greenville. There’s barely a million people in the MSA [metropolitan statistical area].”

Such projects are typically launched with a single substantial tenant, but there was little chance of one emerging in this setting. As Reiter recalled, “I talked to our commercial brokers at the time and said, ‘What’s the biggest lease that’s been signed in Greenville in the last 10 years?’ And they said, ‘Well, it’s 100,000 square feet.’” For context, the building in which Belmont Sayre chose to begin the development, a building originally containing a weave and a picker room — now the Lofts at Judson Mill — was over 300,000 square feet.

Reiter expressed a particular interest in these types of projects. “We think there’s real value in rejuvenating and transforming these neighborhoods that were once thriving. We want to use real estate to have a positive impact.”

Navigating a Textile Labyrinth

Another issue was the complex’s layout and plotting how to approach the site. Almost every structure had been gradually connected to the others, creating a vast labyrinth of a building. Belmont Sayre hoped to trim more of the interstitial links between the original buildings, but negotiations with the National Park Service resulted in just a few excisions, all of which aimed to improve circulation and internal natural lighting while exposing original structural elements.

A photo taken in 2020 shows the interior condition of a portion of the Judson Mill complex before renovation began. J. Silkstone Photography, courtesy of Judson Mill District

The elements removed were primarily the more recent additions to the mill site. A large power station, totaling approximately 30,000 square feet, was demolished to provide space for residential outdoor amenities. Another 16,000-square-foot addition from 1956 was removed to create a public courtyard between the residential and commercial portions on the west end of the site. The rest of the removals were minor — mostly later accessory buildings that had been built adjacent to historic buildings to house air conditioning and mechanical ventilation.

“The buildings also had very large floor plates, which challenged us to come up with a creative design solution that was historically sensitive, impactful and attractive,” Reiter said. “We spent almost a year figuring this out.”

Belmont Sayre was intent on developing a mixed-use project from the start. As Reiter explained, “It gives you a hedge against residential and commercial ups and downs. We quickly surmised that doing commercial development and office development first wouldn’t make sense, so we were committed to making multifamily development work.”

Weaving Apartments Into the Mix

Architecture firm McMillan Pazdan Smith developed a sense of which programmatic uses would be most appropriate for each building. Anthony Tiberia, principal and project manager, explained, “When we saw the original mill buildings that face the street, we felt they would be good candidates for residential development. They’re similar to other mill buildings in the area, which are long and linear, with repetitive structural bays and large windows that make them conducive to multifamily adaptive reuse.”

This was not where McMillan Pazdan Smith started, however. Instead, the Lofts at Judson Mill were designated for the largest building, which originally contained a weave and a picker room. As Reiter related, “It was positioned deep into the site; you cannot see it from the public right of way. We try to take on the toughest piece first because you don’t want to tie all of your financial success to the last phase.”

“It was really this huge, for lack of a better word, pancake,” Tiberia attested. “It was about a football field or more in each direction. It’s a giant square, and it was partially underground.”

“We recognized that the large floor plate was the first problem that needed to be solved,” Tiberia said. “To make the building efficient, we had to provide units in the middle of the footprint, as well as at the perimeter.”

The Warehouse, a 100,000-square-foot building that originally stored cotton, is now home to a variety of office, retail, nonprofit and entertainment spaces. J. Silkstone Photography, courtesy of Judson Mill District

To do this, the architects needed to partially demolish the center of the floor plate to provide interior courtyards that some units could face. McMillan Pazdan Smith worked with the State Historic Preservation Office to determine the size and arrangement. Originally, the firm proposed two large courtyards, but it ended up with four smaller courtyards. “We used these courtyards to provide outdoor spaces for each of these inward-facing units,” Tiberia said. “Even the second-floor units have balconies.”

After tackling these challenges, the rest of the renovation was more typical of other historic mills, Tiberia said. The existing building was in good condition, but it required a new roof. Many of the windows had been bricked in over time, so bricks were removed and new windows installed that matched their historical configuration.

The building’s floors were inadequate for residential use. “Historic mill buildings have thick, multilayer wood floors, which unfortunately transmit sound very well,” Tiberia explained. “To mitigate the sound transmission, you either acoustically treat the floor or the ceiling, which means covering one of them up. Since the original floor was in bad shape, we elected to cover the floors in most cases and open the ceilings. It allowed us to expose all the overhead wood decking, heavy wood beams, and large wood and steel columns. These massive, exposed structural elements are truly what make these buildings special and connect us to their industrial beginnings.”

Other original features remain, including huge concrete buttresses on the exterior of the buildings. “They look like they’re there to support the floors, but in actuality they were often added after the original buildings were built,” Tiberia said. “The reason they’re there is to brace the buildings against lateral movement because when the newer textile machinery was working in unison, it would shake the entire floor plate of the building.”

The Lofts at Judson Mill opened in summer 2021 with a range of offerings, from studios renting at around $1,250 per month to 3-bedroom, 2-bathroom apartments renting for around $3,400. They were nearly 100 percent leased within 10 months.

From Cotton Warehouse to Community Connections

With the lofts completed, the architects moved on to the second phase, known as The Warehouse — preparing a 1990s cotton warehouse of about 100,000 square feet for a mixture of uses, including office, retail, nonprofit and entertainment spaces. Reiter sought to engage tenants who would fulfill local needs.

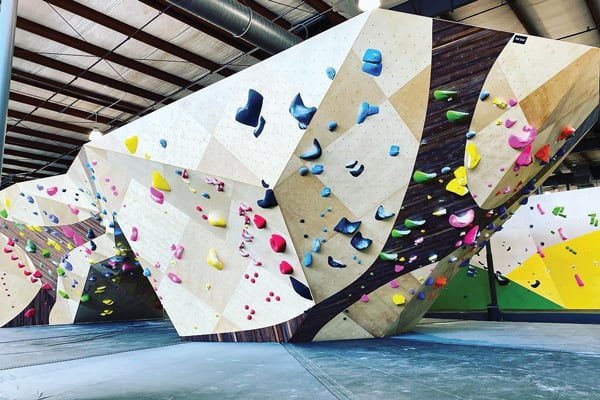

Among the tenants that call The Warehouse home are BlocHaven, one of the largest rock-climbing gyms in the Southeast. BlocHaven

“We reached out to the United Way of Greenville County, the YMCA of Greenville, the homeowners association, the school district and the surrounding churches,” Reiter said. “What we determined was there were three kinds of main pieces missing in the Judson neighborhood, which was a thriving community back in the day.” The identified gaps were access to food, affordable housing and “a total lack of development of minority- and women-owned businesses and enterprises.” The goal, Reiter said, was “to create a space within the real estate development that could facilitate each of those three areas.”

Tenants now include Jud Hub, a socially minded innovation hub connecting social entrepreneurs, community developers and nonprofits; and Feed and Seed, a food hub working to increase access to local foods and establish a sustainable food system built on profitable farms and independent markets. It is also home to BlocHaven, one of the largest rock-climbing gyms in the Southeast; The Foundry at Judson Mill, a music venue; Play Café at Judson Mill, an experiential play space for children; and the Greenville office of site design firm SeamonWhiteside.

The renovation of this building involved different issues than the prior. Tiberia outlined these elements: “The 1990 cotton warehouse was completely different from the other buildings on-site. It’s an enormous steel-framed, open-air building with precast concrete walls, plastic panel clerestories and a metal roof with bagged insulation. Renovating that building was a challenge from an energy standpoint. You have this unconditioned, lightweight building that was meant to store cotton or other raw materials.”

McMillan Pazdan Smith replaced most plastic panels with glass and added considerable amounts of insulation.

The third phase, called The Annex, consisted of more than 100,000 square feet of space, including the original pumphouse and warehouses from the 1910s to 1950s. It was completed in April 2023, with a focus on dining, recreation and entertainment, including Magnetic South Brewing, an axe-throwing venue (Stumpy’s Hatchet House) and more. It will feature event spaces in the former pumphouse, also known as the Smokestack.

“The Smokestack building is truly special because you get to experience everything that makes these mills wonderful,” Tiberia said. “It’s a great big space with a tall roof, large windows and clear structure of brick, steel and wood. Along with The Annex event space, it’s one of the best places at Judson to get a sense of what the spaces were like early in their history.”

A variety of exterior spaces have also been constructed. Private patios adjoin much of the ground floor of the Lofts at Judson Mill. Other spaces are public or connected to various tenants. A pool is between the first and future residential developments, and a courtyard sits between entertainment and residential phases.

“When we started the project, we all realized we needed to adapt the connections between the various buildings,” Tiberia recalled. “Rather than create a fixed overall master plan for the entire site, we took a more organic approach during each phase of development. We left public spaces at the edges of buildings and created interior and exterior passageways where we had to divide buildings or tear down later additions. These new circulation paths were connected to each other at each new phase of development. When the project is complete, not only will these paths connect the buildings, but [they will connect] the site to the overall neighborhood.”

The Final Stitches

Phase 4 will include the renovation of two additional mill buildings, the Westervelt and Jenny buildings (which are about 180,000 and 60,000 square feet, respectively), over the next few years for commercial and residential uses. There are also 12 acres of land for additional development, and the project intends to add more parking.

The site is sorting out to be approximately 60% residential and 40% commercial, which is close to the original estimates for the project, according to Reiter.

Tiberia was pleased with the opportunity to work on the Judson Mill development. “I come from a historic preservation background, so it’s been a fulfilling project to me personally and professionally,” he said. “As Greenville has continued to grow, there’s been a ton of interest from the public to live, work and otherwise enjoy these historic spaces.”

Reiter stressed the long-term commitment it took to return the complex to use while retaining almost all its existing elements.

“There were other developers who were interested in the project. I think there were eight pursuing it. Only two were going to rehabilitate the site, and the others were just going to knock the buildings down and build single-family residential or whatever. That’s just not what we do,” Reiter said.

“Many times, municipalities will have these big complexes, and they think they are sitting on a gold mine,” he said. “What they don’t understand is it’s hard to do a 10-year pro forma and make it work. It’s incredibly complicated, and it takes a unique type of partnership to do this type of transformation. Everybody needs to be rowing in the same direction. … It’s hard to get all of the plates spinning on a stick at one time. Every so often, one of those plates is wobbling. You’ve got to go back and spin it, but that’s also what makes it fun.”

Anthony Paletta is a freelance writer living in New York City.

Looking Back at Judson MillAccording to local historian Don Koonce, creator of the documentary “Building an Empire: The Textile Center of the World,” Greenville had 18 textile mills within less than 3 miles of downtown. “Nowhere else in the world had that many mills that close to an urban center,” he said. Judson Mill, built in 1912 and originally called Westervelt Mill, was the largest textile mill in Greenville County. It was part of the Mill Crescent, a collection of textile mills along the western border of the city of Greenville. When the Westervelt Mill went bankrupt in 1913, its president was replaced by Bennett E. Geer, whom Koonce described as “head of the English department at Furman University and a Shakespearean scholar — [not] totally equipped to come over and take over a textile mill.” Despite his lack of experience, Geer obtained capital to revive the mill from tobacco magnate James Buchanan Duke. Geer renamed Westervelt Mill after Charles H. Judson, a professor at Furman, and eventually ended up running eight mills. Geer also introduced then-innovative rayon blends to Judson Mill in the 1920s, Koonce said. Judson Mill was also “one of the first Southern operations to produce fine yarns and linens,” Koonce pointed out. According to a history posted on the Events at Judson Mill website, Deering-Milliken took over operation, and eventually ownership, of the mill in 1933. “As the textile industry advanced during and after World War II, Deering-Milliken made a series of additions and alterations to the mill complex that allowed the company to innovate. … The company expanded the floor plate devoted to research and manufacturing at Judson by tying together many of the distinctive buildings that originally comprised the complex.” This would prove to be a challenge for Belmont Sayre when it decided to convert the complex for residential use as part of the larger mixed-use development. Judson Mill was once surrounded by its own company town. As recounted by the website, “The history of the mill is marked by a deep sense of community and pride. Mill workers both lived and worked in the community, with everything they needed nearby, like gardens, schools, and even a streetcar stop.” |

RELATED ARTICLES YOU MAY LIKE

Navigating the AI Revolution: A Blueprint for Real Estate Executives

While artificial intelligence reshapes industries globally, commercial real estate is at a crossroads of adapting swiftly or being left behind.

Read More

NAIOP Research Directors Discuss an Industry in Transition

At their annual meeting, research directors shared their outlooks for capital markets, office, retail and industrial real estate.

Read More

Demand Remains High for Construction Workers

Firms with openings for craft workers report challenges in filling those positions.

Read More