An Overview of State Data Center-related Tax Incentives

A 50-state survey reveals different approaches to building out data center capacity.

Even before the advent of generative artificial intelligence (AI), policymakers were quickly discerning that their states’ economic prosperity was linked to the ability of private businesses to store, use and process data. This first realization often came in conjunction with a second one — that states were falling behind projected levels of demand. According to CBRE, during the first quarter of 2024. The cost of space is still rising and vacancies are “negligible,” according to an April report in The Wall Street Journal.

Demand looks set to outstrip supply for the foreseeable future. The industry faces multiple constraints, including the scarcity of raw materials and labor, potential shortages of electricity and a formidable permitting process in many jurisdictions. Additionally, data centers are expected to deliver a larger range of distributed services. This is especially evident in the context of emerging technologies — such as those that power autonomous vehicles or so-called smart factories — that require low latency, large amounts of data and real-time responses. These requirements are difficult to satisfy in a centralized, cloud-based architecture. In the future, a data center network’s geographical distribution — and not just its scale — will likely be a critical factor for the implementation of emerging technologies.

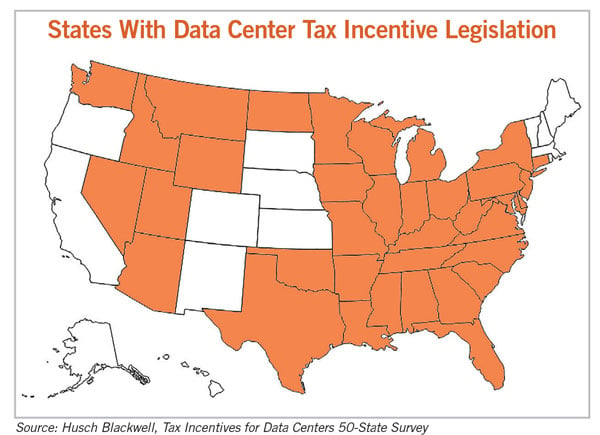

One of the most consequential tools to spur development involves taxes at the state level. Husch Blackwell’s 50-state survey of data center tax incentives summarizes these various state-level initiatives and identifies key differentiating features that could affect the economic viability of projects.

Currently, 36 states have some kind of legislation authorizing tax incentives for new data center development. Some states have been using data center tax incentives for over a decade, but the approach has gathered momentum, especially since AI-related stories have captured the public’s imagination.

As more states crafted legislation, significant variations emerged in how they address key issues, including:

- The kind of tax exemption offered

- The time period covered by the incentive

- The facilities eligible for the incentive (e.g., square footage and parcel requirements)

- Investment thresholds

- The kinds of expenditures or items covered in the legislation

Certain ancillary issues — such as job creation thresholds or security mandates — appear highly prioritized by some states and unmentioned by others, demonstrating the divergent objectives and priorities.

Points of Departure

While nearly all of the legislation included in the survey takes up similar concerns, there is no standard template for how incentives are structured. State laws of this kind are the products of idiosyncratic local conditions and personalities. A common temptation is to view the collection of state tax incentives along the political spectrum from “red” to “blue,” but that sometimes papers over policies that do not fit neatly into a comprehensive — or comprehensible — political point of view. Tax incentives for data centers defy many conventional political labels, and one can find supporters and detractors at all points along the political spectrum.

Each state’s policy must be viewed as a whole to appreciate how it might influence developments throughout the project’s life cycle. A good place to start is the particulars of the incentive structure itself — the kinds of exemptions included and their duration. Some states have been explicit in limiting the period of time that incentives run, usually ranging from 10 to 50 years. Additionally, the duration can flex depending on the nature of the investment. Larger investments sometimes get a longer runway, and new facilities sometimes get the benefit of a longer period than improvements to existing facilities. Several states have not defined a sunset date on incentives.

Just as important as the duration of the incentives is what they purport to cover. Most states have bundled exemptions, and it is important to appreciate what is in the bundle and what is excluded from state to state. Even within the same state, different items qualify for different kinds of exemptions. In Georgia, for example, the purchase and use of high-technology data center equipment to be incorporated or used in a high-technology data center are exempt from state and local sales and use tax; however, the state’s sales and use tax exemptions are subject to different subsections of the law and have different triggers.

The investment thresholds from state to state also offer interesting points of differentiation. Some states have a single threshold level that is applied to all projects; others have tiered levels that tie back to a range of factors, including lower levels for rural areas or new construction, and levels that differ according to the type of investment made. All of these variables should receive the careful attention of tax incentive counsel at the earliest possible point in the project timeline.

Incentives With Requirements

With so much scrutiny aimed at tax incentives generally, it is not surprising to see the presence of requirements baked into legislation that mandate certain community benefits. Of note, several states have specific job-creation thresholds for qualifying projects, and as with other provisions, these vary greatly. Like the investment thresholds, the job-creation requirements are sometimes tied to other provisions. For instance, Nevada’s legislation requires 10 new jobs to qualify for the 10-year abatement; however, the 20-year abatement requires 50 jobs. Additionally, some states require that jobs created cannot be subject to workforce reductions for a specific time period.

Ancillary issues such as job creation thresholds and security mandates are often tied to tax incentives for data centers. Halbergman/E+ via Getty Images

These might seem like modest requirements, but data centers — even large ones — do not require a large workforce to operate. When job-creation requirements are tied to the operation of data centers rather than their construction, the requirements might be hard to meet.

Additionally, provisions often target not just the number of jobs but a variety of other metrics. These typically include mandated salary/wage levels (many use county or state averages as benchmarks), mandated health insurance coverage levels, and requirements that enterprises use state residents for the construction of projects.

Other tax incentive-related mandates selectively put into place by states — almost appearing as legislative afterthoughts — could have a significant impact on projects. For instance, Illinois requires data centers to become carbon neutral within two years after being placed into service. Minnesota defines qualified facilities as having “sophisticated” fire suppression systems and “enhanced” security. Some of these ancillary requirements are negligible to the overall cost structure, but some are material or, at the least, undefined in terms of cost. Project developers and investors should be careful not to overlook their impact.

Wading Into Complexity

The presence of data center-specific tax incentives can be an opportunity for improving a project’s cost structure, but misconstruing key provisions of tax incentive legislation can have damaging consequences after capital has been committed and shovels are in the ground. Additionally, it is important to confirm with localities the presence of general incentives that can also apply to data center projects.

Husch Blackwell’s 50-state survey is a starting point and a useful reference tool, but it is just a snapshot in time. Priorities — and the laws that aim to reflect the same — change over time.

Jake Remington and Rod Carter are partners at the law firm Husch Blackwell.