Bringing It Home: Four Innovative Concepts for E-commerce Deliveries to Consumers

All of these innovations could affect how goods are delivered directly to consumers in the future.

THE PROLIFERATION OF online purchasing has created a vast expansion in the need for delivery of goods directly to customers. One important element in the e-commerce shopping experience has been the streamlining of the fulfillment process, which creates pressure on traditional package delivery mechanisms such as DHS, FedEx and the U.S. Postal Service. Consumers want faster deliveries, but of course do not want to pay for them. Several innovations currently underway will use new technology to solve this problem.

1) Drones. The coolest technological innovation for geeks still waiting for the flying cars long promised by old TV shows, drones offer the flexibility to overcome traffic congestion, poorly connected rural road networks, water bodies and other physical barriers. However, they have limited carrying capacity, currently ranging from 2 to 5 pounds, as well as a limited range of 10 to 30 miles. And they need to return to base after every trip to resupply.

Larger drones designed to carry heavier parcels require a landing area of at least 21 square feet, a problem in dense neighborhoods. Forthcoming federal regulations may impose additional restrictions. These limitations suggest that the most effective deployment of drones for consumer delivery, at least initially, will be in rural areas, which are also the most expensive to serve by ground. Even with these qualifications, a 2016 McKinsey & Co. report, “Parcel Delivery: The Future of Last Mile,” estimated that drones could eventually handle 20 percent of Amazon’s deliveries.

Starship Technologies’ six-wheeled delivery robot is 27 inches long by 22 inches wide and can carry up to 20 pounds within a two-mile radius. This one delivered holiday gifts to residents of Redwood City, California, where the European company has an office. Starship Technologies

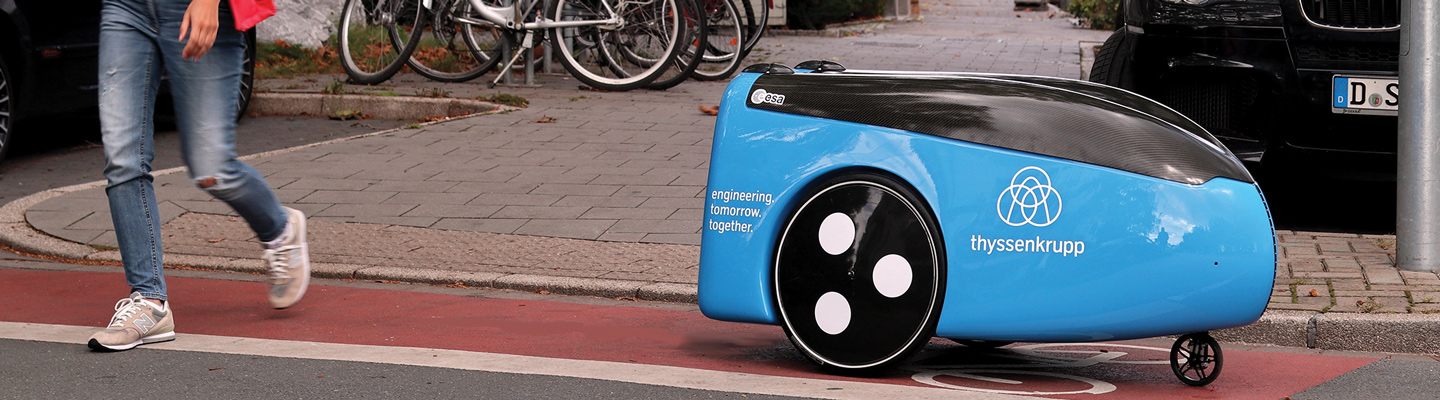

2) Droids. Delivery robots similar to the droids of Star Wars fame are able to travel on sidewalks or in bike lanes, among pedestrians, bikes and cars. Delivery robots can navigate on their own most of the time, making sequential stops to deliver packages to multiple consumers, although a human operator may act as a backup. They have higher carrying capacities than drones and, since they travel on the ground rather than by air, are less expensive and less complex to operate.

According to a 2016 Stanford University white paper, “Technological Disruption and Innovation in Last-mile Delivery,” droids also will face fewer regulations than drones, since automated vehicles and Segways will have paved the way with state legislatures. Droids will be used most commonly to deliver goods to lower-density suburbs, university campuses, assisted living facilities and other private venues. A team of six-wheeled food delivery robots created in Estonia by Starship Technologies is already delivering takeout food from restaurants to customers in Washington, D.C.

3) Driverless Vehicles. The extensive development underway for self-driving cars and trucks could create spinoff benefits for consumer deliveries. In fact, one of the early successes in freight was in October 2016, when Otto’s first paid delivery via self-driving truck was a beer shipment. (See “Six Innovative Concepts for Moving Freight,” Development, winter 2017.)

Pizza would be a natural successor. Sure enough, according to a September 2017 Fortune article, “Will Consumers Actually Like Having Pizza Delivered by a Self-Driving Car?” Domino’s and Ford have teamed up on a pilot project in Ann Arbor, Michigan, to test how people interact with driverless car delivery systems, in a market heavily populated by students. Customers get a text with a four-digit code to access the vehicle when their pizza arrives. Most of the questions about the effectiveness of this application relate to the last 50 feet: Is the car in the driveway or at the curb? Will customers be reluctant to come out into the snow? In fact, these are the same questions that must also be answered for deliveries by drones and droids.

The automated ground vehicle (AGV) is a special variation on the driverless car delivery system. More like a small van, an AGV could be equipped with lockers that could be accessed with a secure code. These vehicles could deliver packages to multiple addresses, and could even be programmed to pick up packages from customers.

4) Crowdsourcing. Although all of the innovations described above involve the delivery vehicles themselves, technology can also be used to speed deliveries to consumers via traditional vehicles. In 2015, Uber introduced a delivery service in New York, Chicago and San Francisco. UberRush promised that “if we can get you a car in 5 minutes, we can get you anything in 15 minutes.” The on-demand delivery service connects bicycle and pedestrian couriers with businesses and individuals. Although Uber closed the service to restaurants in May 2017 – encouraging customers to switch to UberEats, for which it had created a new app – crowdsourced deliveries could have a much wider application for small businesses and individuals.

Walmart, which considered a crowdsourcing system in 2013 that would have enabled in-store customers to deliver packages ordered online by other customers, has begun testing a program that uses its associates to deliver e-commerce orders on their way home from work.

According to a June 2017 blog post by Marc Lore, president and CEO, Walmart U.S. eCommerce, “Associates choose how many packages they can deliver, the size and weight limits of those packages and which days they’re able to make deliveries after work – it’s completely up to them, and they can update those preferences at any time. We also allocate packages based on minimizing the collective distance they need to travel off of their commute to make a delivery.”

Fast or Free? One conundrum created by the e-commerce model is how to pay for the additional costs of delivering goods directly to consumers. This is of particular concern to smaller retailers, who lack the bargaining power that larger firms have with delivery services. Larger retailers are focusing on service speeds, as same-day delivery becomes possible in many metro areas. Shoppers want their goods to arrive quickly, but are averse to paying more to expedite delivery. This is one of the greatest challenges that retailers must address as they exploring emerging technological innovations in delivery to consumers.

By Robert T. Dunphy, transportation consultant; adjunct professor, Georgetown University real estate and planning programs; and emeritus fellow, Transportation Research Board, dunphyefc@verizon.net