CRE Development Opportunities In Public-private Infrastructure Partnerships

Public-private partnerships are emerging as a mechanism that marries the funding of public facilities like courthouses, libraries, government offices and more with private commercial development.

FROM ITS EARLIEST colonial days to its reign today as the world’s largest economy, the U.S. has seen tremendous evolution in how it develops its infrastructure: from the bones of its communities, to connections between its population centers, to the very buildings it constructs to serve public needs. Approaches to financing and delivering the nation’s infrastructure are more dynamic now than ever, with renewed focus on how both the public and private sectors can contribute to infrastructure development.

This article explores the nature of public-private infrastructure partnerships and highlights changing opportunities for private commercial developers in providing the infrastructure that U.S. communities depend on for continued economic growth.

Historical Perspective

For much of the nation’s history as an agrarian society, when a community needed a bridge or road, private citizens stepped up to supply the need, either as a communitywide endeavor or by a private entity building the infrastructure and then charging tolls to recoup its investment. That approach was no match for the demands of an increasingly industrialized society and nationalized economy. Fast-forward to the 1950s, when the imperative was clear for one of the nation’s most significant taxpayer-funded infrastructure investments: President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s interstate highway system. Symbolically and practically, federal highways reflect an aggressively optimistic, bold vision for the nation’s growth and a widely shared belief, at one point in time, that government alone could competently deliver the infrastructure its citizens needed. And, in fact, it did.

It’s difficult to imagine such a bold vision for infrastructure enjoying broad support in today’s political environment. Peoples’ belief in government as a force for bettering their communities and competently serving their needs is strikingly low. This skepticism has translated into dwindling support for broad-based taxes to even maintain existing infrastructure, let alone invest in significant new infrastructure.

Recent years have witnessed shrinking budgets at the federal, state and local government levels that have challenged the public sector’s ability to finance the necessary upgrades to obsolete infrastructure or to develop the new infrastructure needed by a technologically advanced nation. Partially as a result of this ever-widening gap between infrastructure needs and limited available funding, the public sector has increasingly explored new ways to partner with the private sector to design, build, finance, operate and maintain the nation’s infrastructure.

The Basics

Public-private partnerships (P3s) are a model for delivering public infrastructure that is currently enjoying a surge of attention, interest and creativity in the U.S. (They are already quite common in Europe, Australia and Canada.) They represent a long-term contractual relationship between the public and private sectors in which a private sector entity typically designs, builds, finances, operates and maintains a facility intended for a public purpose (a road, bridge, utility, port, parking garage, etc.), in exchange for a payment stream during the operating period derived from user charges, guaranteed payments from a public sector source or, often, both.

Some refer to any form of government involvement in private development — including tax increment financing districts (TIFs), special purpose quasi-governmental district financing and economic development incentives — as a P3. While it’s true that the private and public sectors must work together in those endeavors, this reflects a limited understanding of what constitutes a P3. The key characteristics of traditional P3s include the following:

A Public Facility to Serve a Public Good. The goal of a P3 is to provide a public facility, one that will be used by and for the benefit of the public. It’s a facility that traditionally government would likely have funded and operated completely on its own, if it had the necessary funding and other resources. Public ownership of the facility is typically a key component of P3 structures. No matter how long the private sector may operate it, the facility remains under public ownership.

Design, Build, Finance, Operate and Maintain (DBFOM). From start to finish, in a P3 the private sector is typically responsible for every stage of delivery and will address most, if not all, DBFOM components. While many public entities are accustomed to using design-build strategies to help streamline construction projects, and some may privatize certain operations and maintenance (O&M) services, P3s are far more complex because they contemplate all such accountabilities in a single relationship and transaction.

Life Cycle Delivery System. Aligned with their DBFOM accountabilities, private sector entities are typically obligated to operate and maintain the public facility they contract to build over the course of several decades. They can’t walk away when the project is substantially complete. Rather, private sector partners have to achieve certain performance standards throughout a facility’s operation and, again, at the end of the contractual term when they hand a facility back to the public entity.

Long Term and Large Scale. Most P3 projects endure for 25 to 50 years or longer. This long term is typically necessary to obtain workable financing and to achieve maximum value. Given the complexity of these contractual arrangements, many in the field believe it’s difficult to scale a P3 for projects valued at less than $60 million. Nonetheless, some smaller cities and private sector players are working creatively to achieve similar value for deals in the $25 million to $50 million range, which would make P3s a more realistic option for far more regions and facilities, particularly in smaller and/or older cities across the nation.

Risk Transfer. The onus is on the private sector in a P3 to carry virtually the entire risk inherent in designing, building, financing, operating and maintaining a public facility, from design until the project is handed back to the public sector. Estimating errors and construction delays? The private sector owns them. Construction defects? They own those too. Not as many drivers paying tolls, or as many students enrolling in housing, as anticipated? That’s on the private sector, except when an availability payment model is involved, as discussed below. Equipment failures before the end of their useful lives? More expensive to maintain than expected? The private sector is on the hook for all of that, except, potentially, in the case of supervening events.

Private Sector Capital. If the public sector had all the funds needed up front to build and maintain the necessary infrastructure, P3s would be less enticing. But since it doesn’t, a key benefit of P3s is the private sector’s ability to raise capital. Will they demand a return on investment for use of private capital? Of course they will. But arguably, P3s shouldn’t go forward unless such a delivery model, over time, provides better value to the public, even when one considers the private sector return on investment.

The private sector recoups its return of and on invested capital through some form of periodic payment over the operating term, either from the revenues produced from the facility (demand-risk payments), usually some form of user fees, or from the public entity in the form of guaranteed payments over the term (availability payments), as long as the facility is available for use by the public entity. Often, the revenues are a combination of these forms of payment.

Public-private partnerships offer several key advantages, including the following:

Life Cycle Maintenance. Maintenance needs get short shrift in nearly every public entity’s budget, and public facilities are starved for the kind of investment required to keep them operating in the condition citizens expect but are often unwilling to pay for. Over decades, deferred maintenance can render a building, bridge, school or other public facility obsolete and virtually unusable, well before it should have reached the end of its useful life.

Rebuilding is often the only answer in such circumstances, since large-scale renovations can be prohibitively expensive. With P3s, the public sector gets the benefit of having buildings not only maintained to agreed-upon performance standards, but those buildings eventually are handed back in functional, usable shape — often with next-generation technology and systems in place, lowering future O&M costs. And the public sector gets all this for predictable payments, usually at life cycle costs lower than or equal to traditional public sector delivery models.

As noted previously, the private sector takes on the risk for life cycle costs from project inception through hand back. The public sector gets guaranteed performance, while the private sector bears the risk of production, operations and maintenance. Because it has assumed the risk for decades of O&M, the private sector typically must pay more attention to design and construction quality at the front end. Not being able to hand off the burden after substantial completion provides a remarkable incentive to build for the long haul.

Accelerated Schedules. Because the private sector typically fills out much of the capital stack in a P3 delivery model, as well as driving the design and construction processes, development schedules are far more compressed than they are for typical public sector procurements. Speed simply isn’t what the public sector does best. Shaving months off procurement and construction schedules lowers costs, while bringing in private capital means projects can get off the ground far faster than traditional public sector projects. These compressed delivery schedules mean projects can open and begin generating revenue sooner, further enhancing the value of the P3 model.

P3 Structures

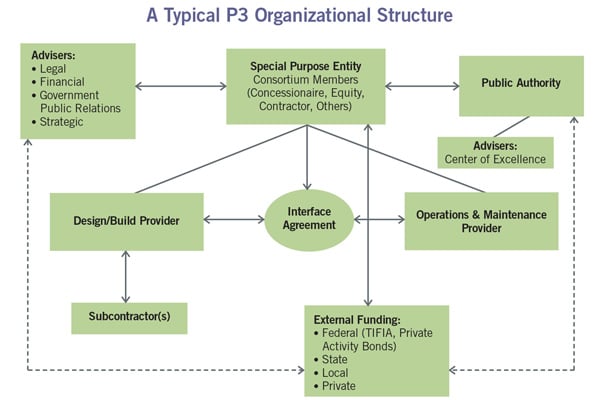

A typical P3 structure will involve the following parties; see the chart above for a graphic representation.

A public sector entity typically sponsors the project.

A private sector entity, typically a consortium or concessionaire, is responsible for contracting with all the parties responsible for delivering and operating the project, including:

- A design-build provider to construct the project.

- An O&M provider to operate and maintain the project over the agreed term, pursuant to agreed-upon performance standards.

- Equity and debt providers to fund the project.

Advisers on legal and financial matters, government and community relations, etc. typically help guide all parties through the P3 process. While concessionaires typically retain best-in-class advisers for these complex transactions, P3 projects tend to run better and provide greater value for the public when the public sector sponsor is equally well advised and supported by subject matter experts.

Lack of sophistication on the public sector side regarding complex financing and P3 structures has at times resulted in projects that didn’t achieve the benefits the public sector thought it was getting, leading some politicians and members of the public to question the wisdom of the P3 delivery model. Recent trends have seen the formation of “centers of excellence” to provide the public sector expertise needed to level the playing field in this regard.

Historically, most P3s have arisen in the transportation industry to provide so-called “horizontal infrastructure”: roads, railways, bridges, etc. Major transportation industry contractors took on these contracts and expanded the scope by adding to their role capital investment and long-term operations/management, a form of turnkey-plus arrangement. In this expanded role, contractors, through their concession arm, would partner with financial investors, operators, designers and other necessary parties to form the project-based concessionaire entity.

By expanding their roles in the P3 context, contractors were able to develop an assured pipeline for their construction business by actually taking on the financial and related operational risks over the long term. Not unlike the movement from the construction industry into the development business in the commercial development world, these larger contractors formed concessions or development arms to expand their businesses in the infrastructure world through P3s.

New Frontiers: Beyond Horizontal Infrastructure

Public-private partnerships in transportation are fairly common even in the U.S., where this delivery model hasn’t been adopted with the gusto shown by other Western industrialized countries. In some respects, the acceptance of P3s in horizontal infrastructure has derived from the fact that it has been easier to figure out how to monetize these types of projects to generate payment streams to concessionaires. The transportation industry has a lot of experience modeling traffic, making it relatively easy to project revenue streams from bridge and highway tolls, for example.

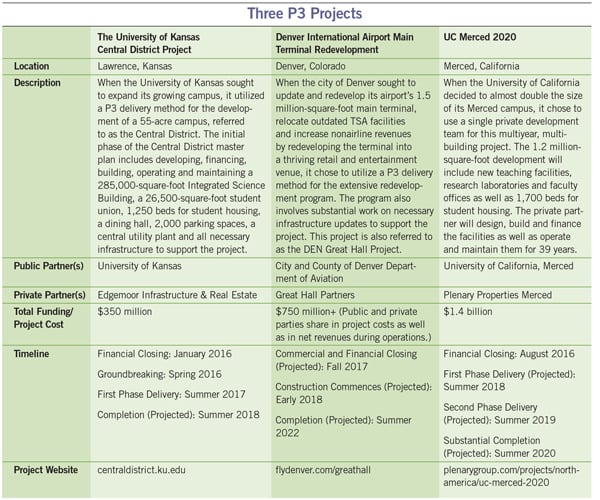

Moving beyond transportation and horizontal infrastructure generally, P3s have gained traction in other infrastructure projects where modeling demand and monetizing the asset are relatively straightforward. Parking structures and many forms of student housing are examples of this expanded P3 reach. Water and wastewater treatment facilities have predictable revenue streams from permitting and service fees.

Demand, which is often captive in these projects, can be consistently predicted; markets are usually established enough to provide good data on pricing; and the projects themselves tend to be discrete, perhaps even ancillary to the core public sponsor purpose, lowering the perceived risk. Prisons are another example of projects that are more easily monetized, and thus more susceptible to P3 delivery. Captive demand, known costs and predictable volume are common features that can be easily modeled for P3 financing purposes, attracting the private sector to these kinds of projects. Such easily monetized assets are, in essence, the low-hanging fruit of P3s.

Newer frontiers for “social infrastructure” P3s include typical public facilities: courthouses and libraries, government offices and other facilities as well as university classroom and research facilities, even entire university campuses. Because assets like these are harder to monetize, they require a more sophisticated P3 model to make the financing work. And because these kinds of projects are often embedded within urban communities, private commercial mixed-use development can be a handmaiden to the central objective of the social infrastructure development project. In fact, it can underpin the financing to make the project financially feasible.

One Example

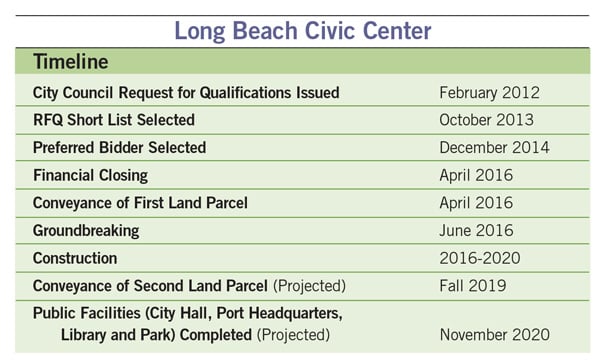

The Long Beach Civic Center project in California is a good example of this kind of creative development, which incorporates private development in a P3 project. The city of Long Beach and the Port of Long Beach needed new office space, in addition to a new city hall and library, as well as new parking facilities and a new central utility plant. Finding purely public funds to build these facilities all at once in a master-planned project would have taken years, perhaps decades, with no guarantee that anything built would be maintained according to desired standards. And, in and of themselves, these kinds of facilities, other than the parking, can be hard to monetize to provide an easy path to P3 development.

To overcome these challenges, the city procured a private concessionaire, Plenary Edgemoor Civic Partners, to work with it in a P3 structure that looked beyond the four corners of the core government facilities to envision a reimagined civic center, energized with vibrant mixed uses to create a new sense of place. As part of the P3 structure, the city agreed to sell the concessionaire approximately 7 acres of public land adjacent to the planned public facility for private development to complement the public facilities.

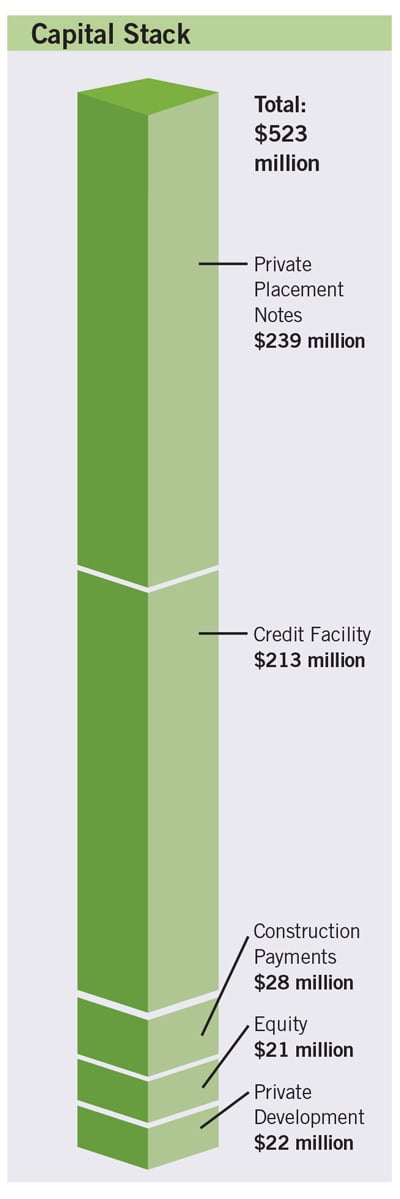

Plans for this private development include hotels, retail space and residential uses. These are seen as key components of the overall project; they will animate the area by drawing people into it. The cash the city received for the land is, in turn, being used in the capital stack for the P3, combined with equity contributions from the concessionaire — a consortium of a private developer and investor — and a cash contribution from the city.

The concessionaire is also arranging the financing, which entails $452 million in private placement notes/credit facility. The concessionaire’s payment stream from the city over the 40-year term of the P3 is no greater than the city would have spent in O&M costs to operate the facilities itself.

This project will provide the city with a vibrant urban core and public facilities maintained to a far higher standard than public funding typically permits. The concessionaire anticipates a substantial return on its investment through its payment arrangement with the city. And private commercial developers will have significant opportunities to benefit from new commercial uses the project has enabled.

Future Prospects

P3s are in the spotlight as never before, as one approach to addressing serious funding shortfalls for building and maintaining public infrastructure, from roads to water treatment systems to university and other public facilities. Right now, those efforts are being undertaken largely at the state and local levels. But new opportunities may also arise in the federal arena, which has had its own success with P3s, such as the Military Housing Privatization Initiative. The U.S. Department of the Interior and the General Services Administration also are advancing pilot P3 programs. Whether the political climate allows for significant new P3 initiatives at the federal level remains to be seen, however.

For now, look for more projects like the Long Beach Civic Center to come online in the future, as public sector budgets remain constrained and the political will to support necessary infrastructure investment remains weak — although cautiously hopeful, given the current administration’s stated priorities. Creative cash-generating approaches, such as off-site private mixed-use development, are going to become increasingly common as both public and private sector players look to new revenue sources to incentivize the private sector to take end-to-end responsibility for public facilities.

Today’s P3 social infrastructure projects reflect many historical traditions for public-private intersections. If both the public and private sectors can leverage project delivery models like P3s to build and maintain U.S. infrastructure most efficiently, all parties have an interest in making sure such transactions are structured for the public’s long-term benefit while letting loose the private sector’s creativity and drive. P3s, applied to the right project for the right reasons, can both catalyze development and facilitate economic growth. They may also bridge political divides and philosophies, to foster an environment more conducive to investing nationally in the infrastructure the U.S. needs to remain the world’s No. 1 economy.

As this P3 delivery model evolves, private commercial development opportunities will emerge as a more important factor in the development of our public infrastructure. Now is the time to take a look!

James M. Mulligan, partner, and Andrea Austin, associate, in the Denver office of Husch Blackwell LLP